poles-1

poles-1

By Jeff Blumenfeld, January-February 2018, skiinghistory.org

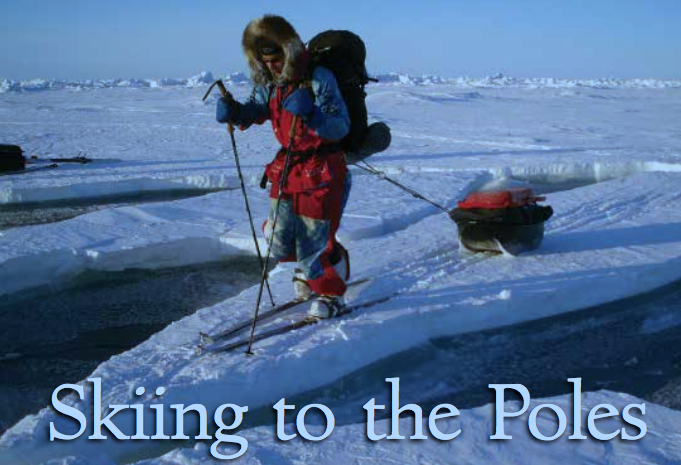

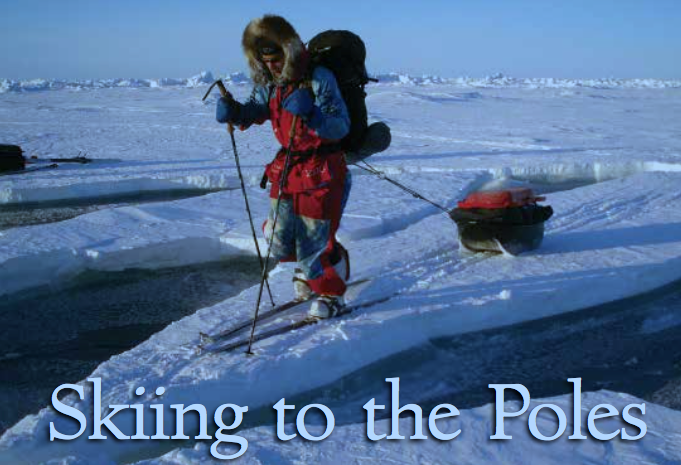

In Part I of this two-part article, author Jeff Blumenfeld explains how skis played a critical role in the early Arctic and polar expeditions of Fridtjof Nansen (Greenland, 1888), Robert E. Peary and Frederick Cook (North Pole, 1909), Roald Amundsen and Robert F. Scott (South Pole, 1911 and 1912). In Part II, to be published in the January- February 2018 issue of Skiing History, Blumenfeld will examine the use of skis in modern-day polar expeditions by Paul Schurke, Will Steger and Richard Weber.

Blumenfeld, an ISHA director, runs Blumenfeld and Associates PR and ExpeditionNews.com in Boulder, Colorado. He is the recipient of the 2017 Bob Gillen Memorial Award from the North American Snowsports Journalists Association, was nominated a Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, and is chair of the Rocky Mountain chapter of The Explorers Club. No stranger to the polar regions, he’s been to Iceland more than 15 times, traveled on business 184 miles north of the Arctic Circle in Greenland, and chaperoned a high-school student trip to the Antarctic Peninsula.

Throughout the modern era of polar exploration, skis have played an in- valuable role in propel- ling explorers forward— sometimes with dogsled teams, sometimes without, and more re- cently, with kites to glide across the polar regions at speeds averaging 7 mph. Modern-day polar explorers including Eric Larsen, Paul Schurke, Will Steger and Richard Weber all continue to use skis today, taking a page right out of history. Were it not for skis, reaching the North and South poles in the early 1900s might have been delayed until years later.

“STARS AND STRIPES NAILED TO THE NORTH POLE”

This long-awaited message from American explorer Robert E. Peary (1856–1920) flashed around the globe by cable and telegraph on the after- noon of September 6, 1909. Reaching the North Pole, nicknamed the “Big Nail” in those days, was a three- century struggle that had taken many lives, and was the Edwardian era’s equivalent of the first manned landing on the moon.

But was Peary first to achieve this expeditionary Holy Grail? To this day, historians aren’t absolutely sure whether Peary was first to the North Pole in 1909, although they are convinced both he and Frederick Cook (1865–1940) came close. Of course, Cook’s credibility wasn’t enhanced by his 1923 conviction for mail fraud, followed by seven years in the U.S. fed- eral prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t until 1986 that the possibility of reaching the pole without mechanical assistance or resupply was finally confirmed, thanks in part to the use of specially designed skis. That was the year a wiry Minnesotan named Will Steger, a former science teacher then aged 41, launched his 56-day Steger North Pole Expedition, financed by cash and gear from more than 60 compa- nies. The expedition would become the first confirmed, non-mechanized and unsupported dogsled and ski journey to the North Pole, proving it was indeed possible back in the early 1900s to have reached the pole in this manner, regardless of whether Peary or Cook arrived first. Dogs are the long-haul truckers of polar exploration. For Steger’s 1986 journey, he relied upon three self-sufficient teams of 12 dogs each— specially bred polar huskies weighing about 90 pounds per dog. The teams faced temperatures as low as minus 68 degrees F, raging storms and surging 60-to-100-feet pressure ridges of ice.

To keep up with dogs pulling 1,100-pound supply sleds traveling at speeds of up to four miles per hour, team members used Epoke 900 skis, Berwin Bindings, Swix Alulight ski poles and Swix ski wax, according to North to the Pole by Will Steger with Paul Schurke (Times Books/ Random House, 1987). In its basic equipment, this mode of travel was not far removed from the early days of polar exploration.